The momentous tilt that brought greater productivity can be dated with some specificity through art and literature from the period.

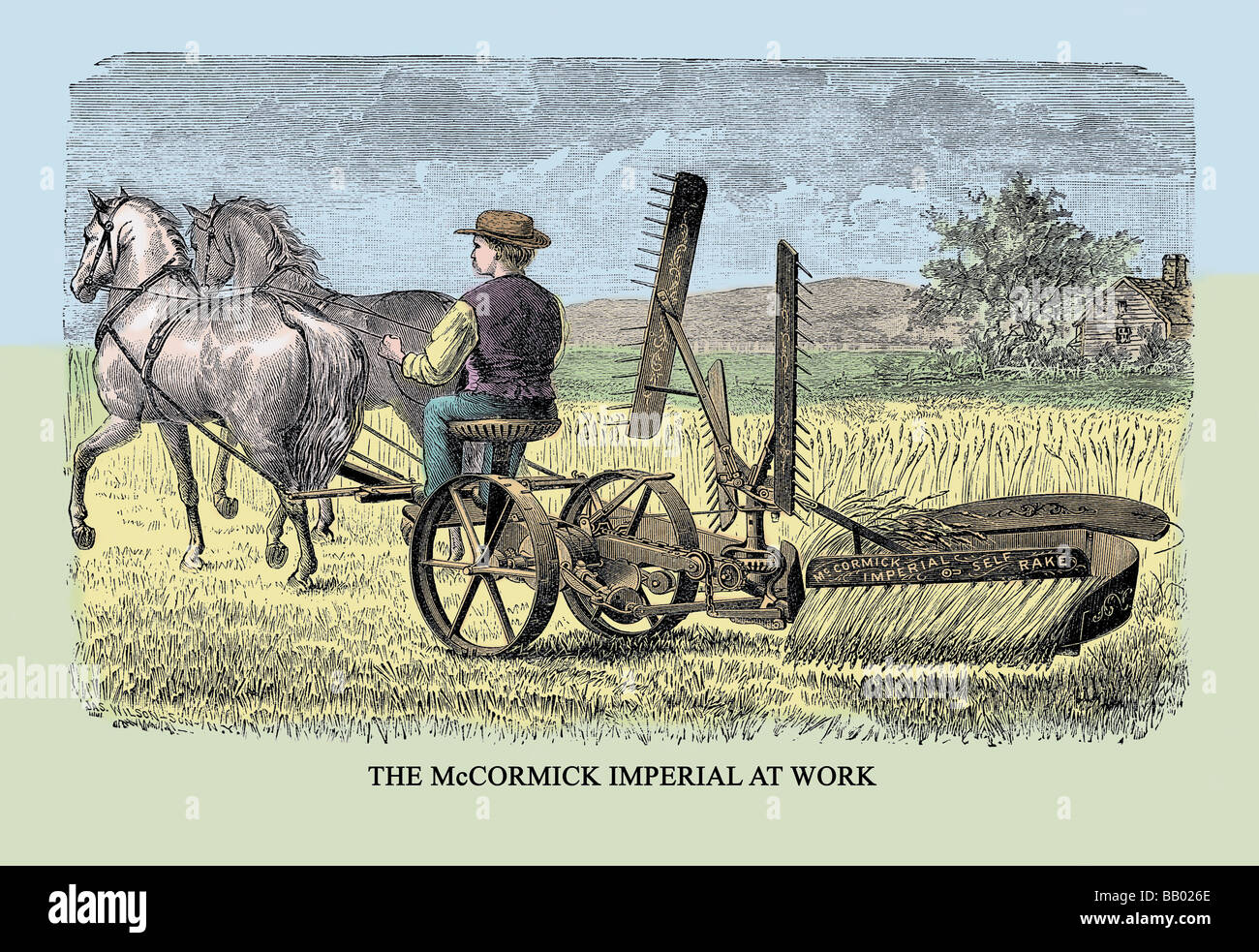

“Reaping at Syracuse,” Harper’s Weekly (August 1, 1857) Top: Reaping in the Olden Time Above: Reaping in Our Time (1857) The inexorable shift to technological modernity eclipsed eons of social and economic relationships that had guided human endeavor since the beginning of recorded history. But the ancient grain varieties native to Europe for thousands of years and introduced to the New World as early as the 1500s remained essentially unchanged until twentieth century plant genetics spawned hybridized cultivars resistant to shattering and lodging. While some loss of kernels took place as grain heads could shatter from the reaper’s wooden reel paddles, the stalks were effectively captured to be bound, carted, and threshed. The effectiveness of mechanical reapers like Manton’s and my grandfather’s equipment led to their widespread use throughout the country and subsequent improvements further reduced the need for rural laborers and rendered traditional field gleaning virtually impossible. Although the old McCormick reapers on the hillside above our house had largely been invaded by the branches of cherry tree, a skinny youth could still wiggle down between wooden draper roll and outside iron wheel and dream of driving a tank.

When Manton told me about playing on the old horse-powered mechanical reaper it instantly brought back memories of my own Palouse Country boyhood. I couldn’t help but smile at the special childhood memory brought to mind recently when local historian Manton Bailie, lifelong resident and farmer in rural community of Mesa, Washington, showed me some old farm equipment in rusty retirement at this place.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)